[Editors Note: This post was originally part of a National Geographic photographers series from 2011. You can also check out others from Jim Richardson, Jodi Cobb, and Joel Sartore!]

Crossing the Yellow Border

I’ve been photographing for “the yellow magazine” since 1987, and that land beyond the yellow border is indeed a wonderful, and strange, place. It contains and defines the entire realm of experiences—impossible odds, magnificent occurrences, unprecedented access, nearly unbelievable bad fortune, outright danger, the exhilaration of the hard won chrome or file captured, and the devastation of bad days, or even weeks in the field.

That place, “in the field,” can be the urbane and sophisticated streets of Paris, or someplace literally so remote as to have never felt the footprint of man. It can be the ultra-sacrosanct tombs and structures of societies time has all but forgotten, or the blinking, humming computers that power our most modern technologies. The magazine’s official mission statement is “to increase and diffuse geographic knowledge.” “Geography,” for the editors there, generally encompasses both physical and cultural geography. People and their places. People in relationship to the planet. The planet itself, in all of its’ magnificence, and wreckage. The earth, sea and sky, and all the organisms those elements nurture, and occasionally, punish.

In short, everything. Trust me, I know this first hand. I was once given a story to do called “The Universe.” Yikes. (To my editor, I was like, “Okay, how long do I have to shoot this?”)

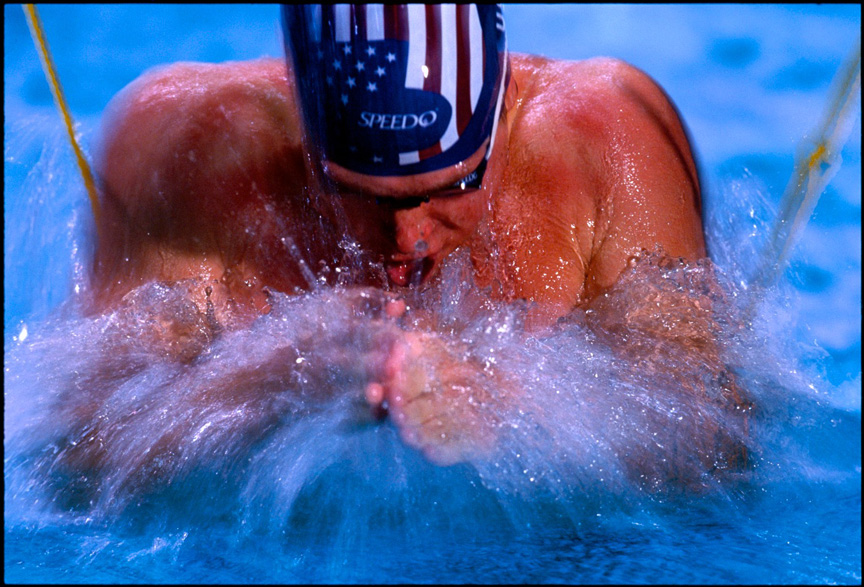

I was already an established “New York” shooter, with covers of Sports Illustrated, LIFE, Time, Newsweek, New York, etc., by the time I came to the attention of the yellow border gang. Strategizing to get an assignment, I turned down a go everywhere credential to the Seoul Olympiad for Sports Illustrated to honor a commitment to a week long freebie speaking tour called The Flying Short Course, sponsored by the NPPA. Sounds unbelievably stupid, right? A freelancer turning down a month of day rates to keep an obligation to do a series of free lectures.

On the face of it, yes. But the method to my madness involved being on the same touring faculty as Tom Kennedy, then DOP of Geographic. I had the opp right then and there to show my portfolio to Tom, five days in a row. I gulped, said no to SI, didn’t’ go to Seoul, and instead went off to lecture. At the end of that week of touring and talking, Tom looked at me and said, “You should come down and start shooting for us.” That was 1987. Still shooting for them. Finished my last assignment this past summer. Almost 25 years, and lots of yellow boxes, and pixels, later, I’m still out there, trying to increase and diffuse.

That longevity was not a given, to be sure. It never is in the world of freelancing, and I did my best in my first few efforts for NG to ensure my career with them would be truly short lived. I made big time screw up after big time screw up.

It was a different type of shooting, you know? I was used to the New York method. That kind of played out like this: Get a phone call from an editor at a weekly publication in Manhattan. Say yes. Never, ever be able to reach that editor on the phone again. Make all the arrangements, Go shoot the job. A week was a long time. Six pages was a big story. Get in, get out. Process film. Deliver it in a breathless rush. Not hear anything. Call three weeks later. Finally get the editor on the phone. “Oh, hi. Yeah, Joe! It is Joe, right? That story that you shot? Oh, oh, yeah. Oh, yeah, uh, it was good, we liked it. Thanks. Gotta go to a meeting.”

Have phone ring back, almost immediately. It’s a call from that very same editor you were just talking with. That editor who now all of a sudden remembers you, and realizes you are standing there, somewhere, with enough time to make a phone call and this qualifies you as a warm body with a camera, and potential availability to solve a problem the managing editor just threw on his desk like a big, steaming turd. “Hi, yeah, uh, by the way, are you busy in the next two hours?”

You laugh. There was a very nice gentleman at Newsweek named Ted Russell, who used to routinely call at the last minute. “Hi, uh, Joe. Uh, it is Joe, isn’t it?” “Yes Ted.”

“Good, uh, Joe. Say, you think you could get an assistant and your lights to Capetown, South Africa in the next 12-18 hours? We’re crashing a cover on Mandela.”

“Ted, does Mr. Mandela know he’s being shot for a cover?”

“Uh, no. But we figure you’ll work that out on the ground.”

Geographic did not work like that, and still doesn’t. Geographic is considered, not breakneck. Geographic ponders, as you would expect they would, doing stories not for tomorrow’s paper but for a pub date that is sometimes two years out. Watching a story develop at NG is kind of like watching one of those slow, shuffling herds of elephants moseying through the savannah, clouds of dust everywhere, that are routinely portrayed on the Nat Geo TV channel. In contrast, shooting for New York based weeklies, at least when I started, was kind of like being a squirrel on speed.

The first thing I was assigned to do for National Geographic was a “fix” on a story on Washington State. I was given three weeks to shoot this. Three weeks to shoot a fix? Holy sh!t. What was broke?

Whatever it was, I was told I broke it even more. I was crushed. First time out of the gate, and I flopped. I, of course, was more upset about it than they were. I thought it was over before it began, but then they called me back. They had a package of stories they were working, on immigration, and would I be interested in shooting the historical port of entry, Ellis Island? Small story, by their lights. Fourteen pages. Gave me a month to shoot it. Yikes.

It was a home grown story, sitting out there in the harbor. I began to get up every day at 3am and trek my way to this frigid, largely abandoned island. No people. Just me, the rising light, and the ruins of what was once one of the most bustling places on earth.

Of course, I knew why they had called me back. The main building of the island, the Great Hall where all the immigrants were processed, had to be shot. At the time, it was being renovated, and was a powerless, under construction shell. So, to shoot it, I had to light it.

It was the biggest lighting job I ever tried. About 65 power packs, and about 100 flash heads. Couple hundred thousand watt seconds, all going off at once, powered by a huge generator truck, which I got onto the island by dishing $1000 cash under the table to the construction site super. That was another reason to hire me. I knew how to work in New York.

It was December in the middle of the harbor. Power packs were freezing, I was freezing, and my beleaguered crew was damn near mutiny. It took four days, virtually without sleep. I’d shoot sunrise, and then have to process the film, and make adjustments. By the time the adjustments were done, it was time for sunset. So it went for almost a week, just to get one frame, which ultimately ran a half page. For this effort in the field, Nat Geo paid me $250 per day.

That was it. You see, I wasn’t really a Geographic shooter yet. I was in test phase, you could say. They would pay you minimally, a kind of entry level wage, during your first efforts back then. Kind of like throwing a very small bone into a snarling pit of freelance photogs, and stepping back and seeing who comes up with it, which I’m sure was an entertaining process to watch. The Geographic illustrations editors didn’t much want to work with a newbie, either. The budgets on these jobs made them cautionary items indeed, and while you were in the field, you basically had your editor’s job security in your back pocket. You fail, and they would take heat back at the ranch. Hence, many were hesitant to work with a rookie. They wanted Stanfield, Richardson, or Johns. All tried and true veterans, who knew how to deliver their style of coverage. Understandable.

I found out downstream that Ellis Island was well received. During the job, my editor was pretty inert. He would take my calls only occasionally, and rarely returned them. I didn’t go to DC for a big showing, like I had been told about. I just shipped in my Kodachrome, and waited for judgment. Cool by me. No different than working in New York!

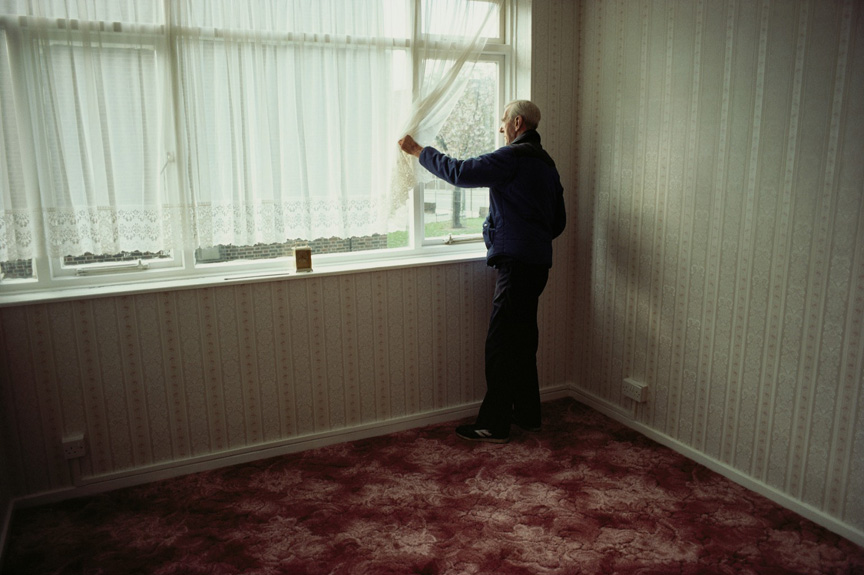

Then, Kennedy called me in. There was another story in trouble. The shooter had missed by a wide mark, even after weeks in the field. The story was London Docklands, also a large construction site, this one on the River Thames.

Tom looked at me. He said, “We’ve already done this story and failed. Many editors here feel there is no story there, but the managing editor feels strongly about it, which makes it precarious for you. If you fail, you’ll never work here again. But, I want you to take this story.”

How could I say no to such a cheerfully described opportunity? I toddled off to London for 17 weeks, at $250 per day, with only one break to come home. I was given an editor who was basically retired at work. She was quite fond of the original shooter on the story, and disliked this turn of events, and hence, me. So, she gave me none of the research that had already been done, and did not look at a single frame of the nearly 1,000 rolls I shot.

Thankfully, back then, Geographic had film review. It was a check and review stop your film passed through to make sure your cameras were working, and all things technical were on the up side. Kennedy, knowing my editor was out to lunch on this one, would wing through there and grab a view at a few frames, and tell them to call me with this message. “Tell him he’s failing.” He was sincerely trying to be helpful, in his own blunt way.

I thought I was going mad. I looked through the lens listlessly. Then, Sam Abell saved me. A wise, veteran shooter, I sought him out in my one break, and showed him copy Polaroids of my Kodachromes. I told him I was flat out crashing and burning, and in the field, I was like an airplane pilot who had lost altitude, airspeed, and ideas, all at once. Sam looked at the lot of postcard size images. He turned to me, and said, “Joe, just keep doing what you’re doing. The photography’s well in hand.”

That’s all you need somebody to say, right? Thus buoyed, I actually had the strength to pick up the camera again, and I bore down for the ensuing stint of nine straight weeks in the field. The story got upped in page count, which meant they liked it.

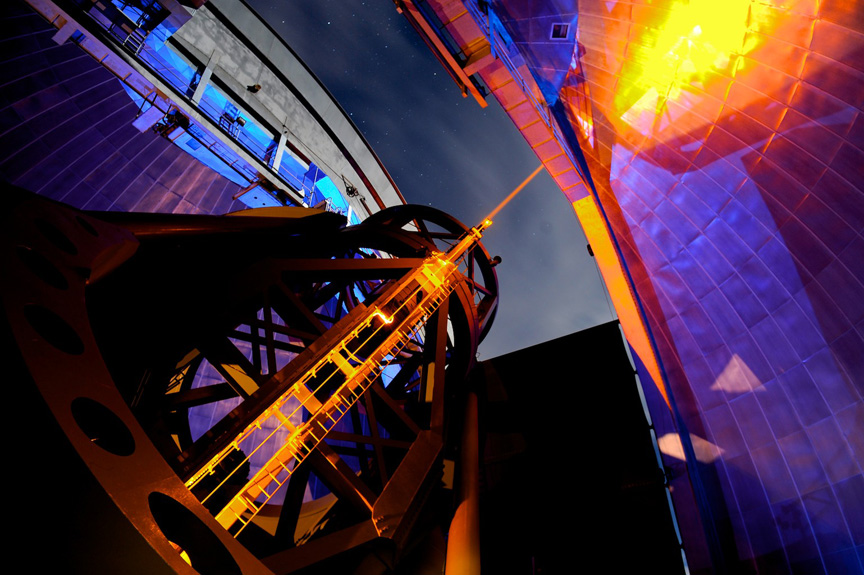

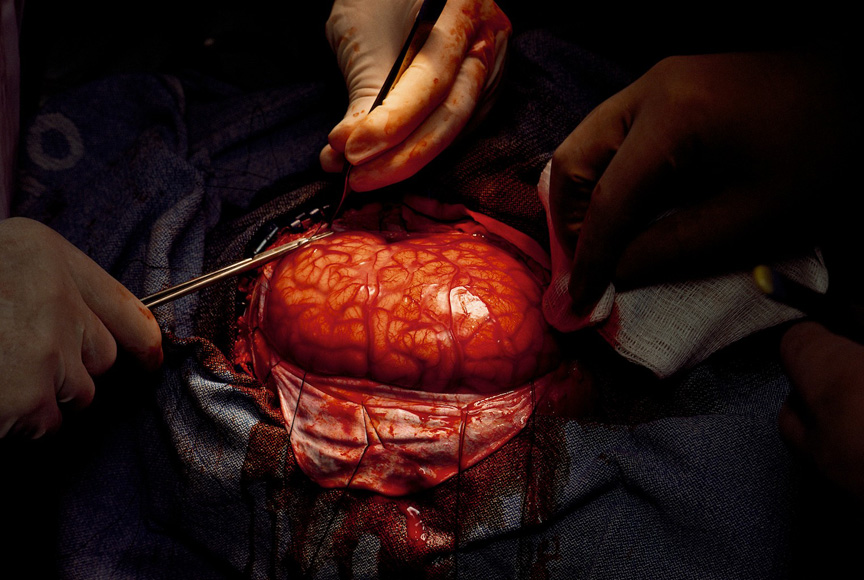

Kennedy called again. No story in trouble this time. It was a science story, called The Sense of Sight.

It was a round the world opportunity to examine the phenomenon known as human vision. Can you imagine? As a photog, I got a chance to study, shoot, and explain to others the marvel that is the human eye. The contract was for 26 weeks, at $500 a day. It was like getting called up to the bigs from rookie league ball. It remains the most complete opportunity I’ve ever had as a shooter. The proving ground had worked. I’d passed my tests. They were now really willing to risk something big on this bedraggled numnuts of a NY shooter. And I do mean risk. The bigger stories at Nat Geo had price tags way into six figures. Lots of planning, research and dough went into putting you, with a camera, in a place where the wild pictures are.

It also brought me together with Bill Douthitt, who has been my editor, and friend, on ten stories over the years. A true renaissance man, he knows more stuff about more stuff than just about anybody I know. Having him in your corner, shaping the story, editing your images, listening to your rants, and re-directing your overheated imagination, is what it means to really, truly collaborate. He’s always been a source of support and encouragement.

For instance, he once wrote to me that “a perusal of your latest take indicates you’re approaching the story with the zeal and vigor generally associated with the better varieties of shrubbery.” It’s basically like working for @ShitMyDadSays.

It’s not an easy passage, this yellow border crossing. There’s heartbreak and failure along the way. There’s emotional discord and stress, both in the field, and at home. There’s constant risk, and exposure to things that are strange and new. (Which is great fodder for photographic zeal, to be sure, but fatiguing at the same time. After four or five weeks of eating stuff you don’t ask questions about, sometimes, you just want a cheeseburger and a coke.)

There’s loneliness. Sometimes you are in a place where you can only communicate with your fixer, and virtually no one else, given language barriers. Given the ongoing stress of feeling like you’re shooting garbage, you get literally jack hammered by your own uncertainties and insecurities. (Feel nervous about digital storage, and not losing your images out in the field? Try shipping 75 rolls of Kodachrome back to DC from Mumbai in a bag. When I would do stuff like that, I literally could not eat until I got word the film had arrived safely.) You travel by yourself, cross dicey borders, get harassed and questioned. Anyone out there who thinks a letter of assignment from National Geographic confers upon the bearer a Moses-like ability to part waters and make great pictures happen, is just, well, wrong in that assumption.

It’s not for the faint of heart, in short. There are photographic rewards, to be sure. That sight assignment was exactly as Kennedy described it on the phone to me that day. It was a gateway. Cross this bridge, and school’s out. You can call yourself a Nat Geo shooter.

At the behest of the magazine, you see marvelous, not to be repeated things. You witness the great trends and developments of our time, and turn your lens on stunningly beautiful stuff, along with heart breaking moments. You observe the tilts and whirls of culture, science, nature, and human behavior in a special way. And you bring back visual dispatches that become a window on the world for some 30 million pairs of eyes. Very cool, and, a huge responsibility. You also live in fear that when the moment happens, the one you’ve come for, you will miss it.

And, here’s a small thing, a perk if you will, of pushing yourself down this occasionally precipitous and never smooth road. You get to be in this small group, a club, that carries a very hard won membership card. For the last 30 years, the folks who have pulled the picture wagon for the yellow border magazine number no more than say, a hundred.

Every year, in January, the yellow magazine calls together its’ shooters for a couple days of meetings. There is a photog’s lunch, and we are a small number, in a relatively small room. There is, in addition to exhaustion, tension, and uncertainty about the future, a ripple of quiet pride in the room. There’s also jealousies, bad feelings, and huge egos. After all, it’s a room full of photogs.

At the beginning of the lunch we have been traditionally asked to go around and say no more than an introductory sentence or two about ourselves, in case there are new people there. It passes around, and people simply say something like, “I’m so and so, and I just shot the recent cover on such and such.” Or, “I’m so and so, and I’ve been shooting for the magazine for 22 years.” Bits and pieces like that. Snippets.

At the last one I was at, a very esteemed and talented photographer, a mainstay of the business for many years, who for some reason never had the chance to shoot for the magazine, was there. That year marked his first published coverage and thus his first invite to the lunch.. He introduced himself. “I’m….”

Then he paused, smiled, and looked around the room. “And I’ve been waiting the longest to be in this room.” He sat down to applause.

More tk…

You can see more of Joe’s work at JoeMcNally.com, keep up with him on his blog, and follow him on Instagram.